Introduction

What do you think of when I say “the four cardinal directions”? Does your mind shift to geography class or flashback to the olden days of yore when we used to use paper roadmaps instead of GPS to find our direction? I might pose the thought that, in this day and age, directions may be seen as having become “out of fashion” and almost obsolete. As we have become more dependent on technology and machinery, it could be said that generationally many of us have lost touch with nature; we have also lost touch with knowing the signs of which way is north. And yet, just like how I might suggest to put down your cell phone and have an older family member or friend to teach you the ways of the sky, I might also suggest considering the cardinal directions and the ancient meaning that they hold.

Since college, probably, it’s been my bent to never just read a book—but to think critically while reading through it. Picking up patterns, asking questions, trying to connect to the author’s intention, these are all a part of my reading style (for better or for worse). While reading C.S. Lewis’ The Voyage of the Dawn Treader this time around, I was particularly attracted to how directions in the story played a significant role in the character and plot progression. The directions seemed to have some kind of hidden meaning behind them (true to Lewis-ian form) that I just wasn’t getting, so I dug around for more information. And let me tell you, there is nothing like searching for knowledge to make you feel ignorant. On the other hand, there is nothing but the search and finding of knowledge to make you less ignorant (although I don’t think the feeling ever goes away). An entire world—a world that those more connected to the elements than me have long since known—was opened up to me, and Narnia’s pages once again took on a new form.

Just like with the other Narnia books, Lewis gives us glimpses of biblical truth and reality through the lens of fiction. In this article, we are going to explore the cardinal directions as a connective theme for Narnia, discuss the biblical symbolism and history surrounding Old Testament geography, and then analyze how Lewis may have used the symbolism to add another layer to the allegorical nature of Narnia. We’re going to talk Bible; we’re going to talk history. We’re going to talk symbolism; we’re going to talk Narnia. So, let’s dive into this.

Theories of Connective Themes of Narnia

While it’s the readers’ role to dig deep and take ownership of their experience with the book, there will always be a slight (or huge) dissonance between the author’s intention and the readers’ thoughts of the author’s intention. While some readers are quite able to throw caution to the wind and allow all of their thoughts to roam freely amongst the setting of the book—throwing around and adding thoughts, ideas, and their own fingerprints to the creation of the book—I’ve always been a more hesitant and cautious sort. That being said, I admire those who have those talents, but the author and designer inside of me can’t seem to let be that the author intended one thing and, unless I know specifically with evidence what that one thing is, I am likely just to put all interpretations in the “I don’t know” category. And yet, I love that category (for reading, at least—real life, not so much), so I’m content with exploring some of those thoughts here in these articles.

The Seven Planets

Lewis’ books have been the subject of many a debate in terms of their interpretation or a general overarching theme that joins all of the books into one fluid thought. J.R.R. Tolkien himself seemed to find his friend’s books lacking in cohesiveness and consistency of history and themes (“Planet Narnia,” n.d.). One thing is for sure, though: we sense that there is meaning behind the chaos, but Lewis keeps it just elusive enough to keep us guessing and wondering. As is the case with good writing and even infamous writing, critics, academics, and romantics are fascinated with finding comprehensive design and a key to unlock the mystery. One such theory connects Lewis’ Narnian works with cosmology. While this is not the main focus on our article, it’s a fascinating connecting point and probably one of the most well-known theories, so I think it is valid to give it some room here.

Lewis, with his interest in medieval cosmology thus being seen in his works such as “The Planets” and The Discarded Image, has been accredited to crafting the Narnia series with the seven medieval planets—Jupiter, Mars, Sol, Luna, Mercury, Venus, and Saturn—as the key to its interpretation. One planet, complete with its cosmological theme, is dedicated to one book, thus seven books for the seven medieval planets. For example, Jupiter is attributed to winter passing, which can be seen in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe through the change from winter to summer (Lezard, 2010; Christopher, n.d.; “The Seven Heavens,” n.d.). The full depth of this theory can be found in Michael Ward’s book Planet Narnia. While this theory may or may not be the true intention of Lewis, it is a fascinating thought to consider and evaluate while reading through the books.

The Four Directions and Time

Stepping into this article’s theme, another “key” that could be explored as opening up Narnia as a collective whole is the four directions. Narnia has been described as an “expanding universe,” much like Star Wars or Marvel. In other words, it is a universe where its genesis story (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in Lewis’ case) has been wrapped up in a novel or movie or two, but there is still plenty of room for extension. And thus, wonderful appendages are brought into existence. Generally, there is growth stemming from the exploration of time and direction in an expanded universe, and Narnia seems to follow in line with this theory. Not only that but true to our topic and in similar form to the above theory, Narnia’s novels can be seen as each exploring a cardinal direction and chronal direction.

1. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, as the genesis novel, gave birth to Narnia.

2. Prince Caspian dealt with those from Telmar, which is in the west.

3. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader had Caspian and his crew heading east to Aslan’s Country.

4. The Silver Chair has Polly, Eustace, and Puddleglum journeying north to find the lost prince.

5. The Horse and His Boy took place in Calormen, which is to the south.

6. The Magician’s Nephew dealt with the extreme past, as it chronically takes place before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

7. The Last Battle finished up the series with the end of time. (“Literature / The Chronicles of Narnia aka: Narnia,” n.d.)

As mentioned before, whether Lewis intended for this representation within the books, it can’t be known, but like the concept within Planet Narnia, the thought itself draws together a cohesiveness that perhaps some would say is currently lacking between the books. That which adds potential dimension and depth to a book or series, as well as giving the reader a chance to engage with that world in a new way, is often worth the thought. For this article, we will be focusing on the cardinal directions as our connective theme to think deeply on Narnia and to engage with some playful thought regarding the amazing Spirit-led words of the Bible.

Four Cardinal Directions in The Chronicles of Narnia

While each book seems to be rich in symbolism for each of the four cardinal directions, for this article, we will just be analyzing one representative book for each direction. While this idea of an expansive universe is worth an expansive article (and I’m sure you’ll get one nonetheless), for the sake of coherency, I will not be discussing the genesis book or the books associated with the direction of time. Thus, let’s focus on the four directions and their associated four books: Prince Caspian (west), The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (east), The Silver Chair (north), and The Horse and His Boy (south).

Perhaps you have gotten this far and are currently underwhelmed with the topic. Likely, that is because I have not described the biblical symbolism that can potentially be seen for each direction. I haven’t described the meaning behind each direction or tapped into that fascinating land of interpretation. In this main section, I will give a brief introduction to the biblical symbolism for each of the four cardinal directions—while sometimes introducing geographical and historical information to add validity—and then do a brief analysis to show how Lewis is potentially using the biblical symbolism to create a further level of complexity to his novels and take readers deeper into spiritual consideration.

Note: While it is one thing to interpret Narnia or fiction books, it is another thing entirely to interpret the Bible. I am not a biblical scholar, and I am not academically trained in interpretation or the Old Testament, therefore, I want you to recognize that there is potential for a lack in the research I did for this article and its presentation. For those out there who know better than me, I would love to engage with you or be directed to more reputable sources.

There are truths existent in the Bible and its interpretation that are non-arguable in terms of traditional Christianity (first-tier issues such as Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, the Trinity, etc.); however, there is a great deal of mystery to the Bible as well, because we can only understand so much of the God who created the entire universe. While we should never be tempted to sway from the founding truths of our faith found in the Bible (although, our faith should be our own, and therefore, we should question all of those truths, ask the Holy Spirit and wise counselors for guidance, and have a research- and experience-based reason behind why we believe what we do), I believe that there is room to ponder on the mysterious. To me, this is an academic exercise that I hope will help potentially give you something new to explore and stir up affections (or at least curiosity) for our Lord who is infinitely larger and more complex than we can imagine and a love for the revelation given to us by Him through His Word. And if that is not for you, hopefully, we can just have some fun talking about Narnia.

The West

This direction pairs with its eastern counterpart, and it holds both light and dark meanings. The sea was found to the west; and when mentioning the “sea,” Daniel 7:2-3 seems to be referring to the west. This direction is attached to the idea of evil and death. As the sun rises in the east, it sets in the west, and therefore, there is an association with darkness to it as well. (Rodríguez, 2008)

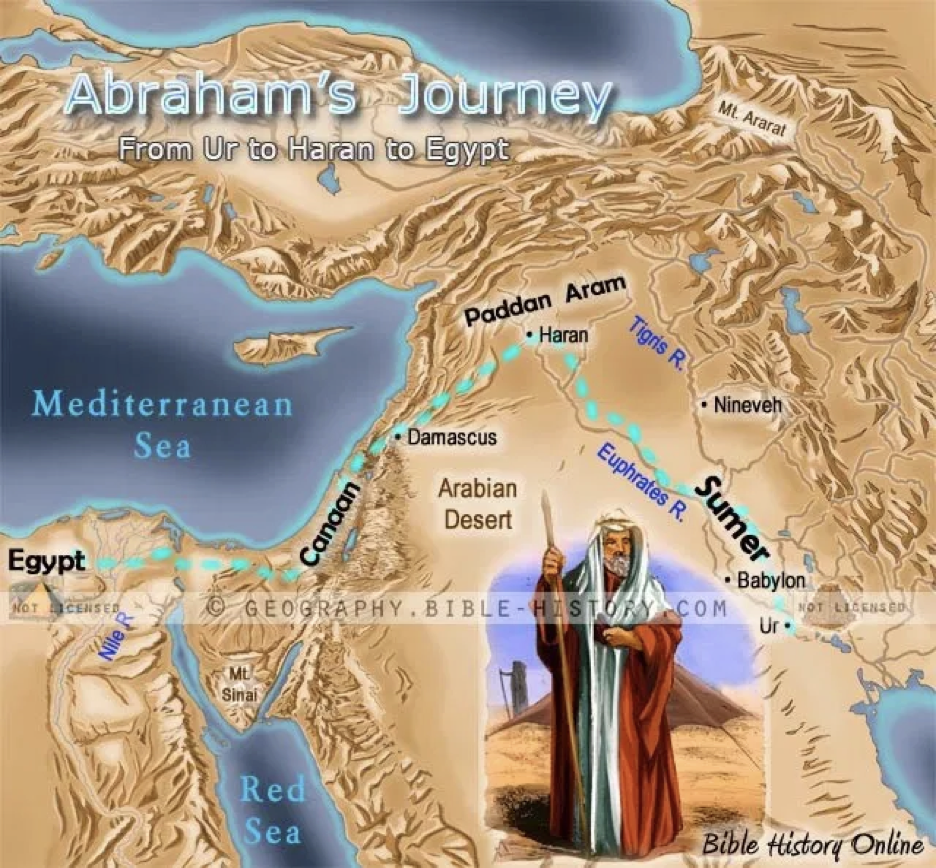

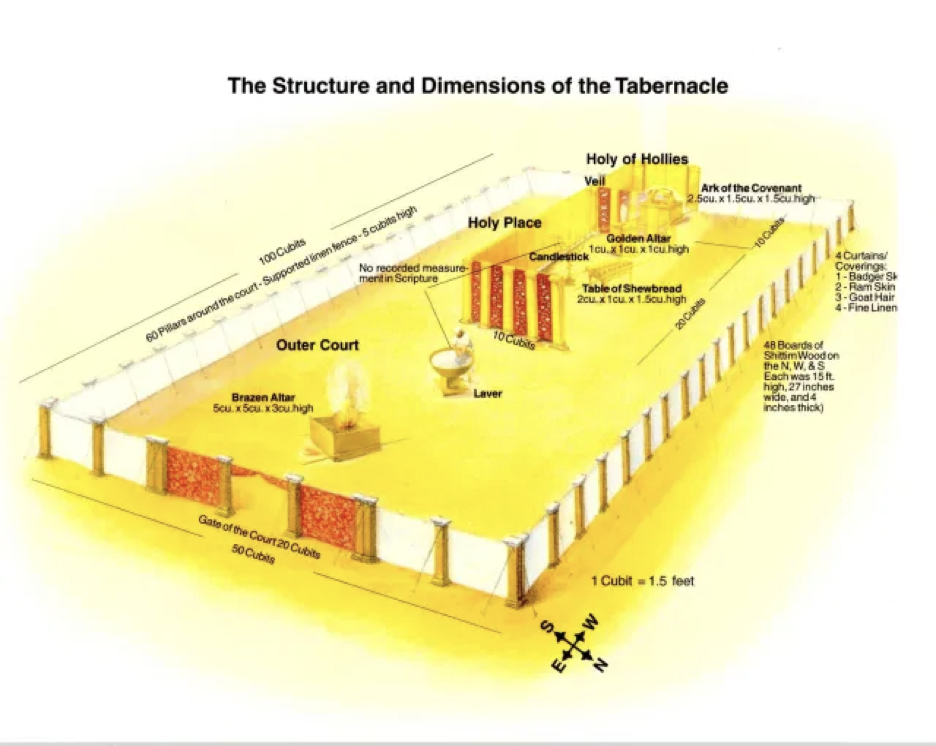

Positively, though, while the Tabernacle faced out toward the east, one had to journey west to gain access to it. As will be discussed further in the section regarding the east, heading west alludes to a reuniting with God. In Genesis 11:31, Abram began journeying to the west, heading toward Canaan as per God’s instructions.

Following later in the Old Testament, when the exiles were released from the oppression of the Babylonians of the east, they traveled with God to the land of Israel in the west.

Book Analysis: Prince Caspian

Caspian X, one of the protagonists of the Narnia series and king of Narnia during Prince Caspian, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and The Silver Chair, is by lineage a Telmarine. While the history of Telmar is a complicated one, it seems that Lewis is expanding his map to the west through his introduction to the country. As was described above, the west is seen to be symbolically linked to the “sea.” Due to Telmar having roots in being a seafaring pirate nation, it would make sense that its naming origin may come from the Greek word tel (“far”) and the Latin word mare (“sea”). As it seems that most of the directional guideposts find their epicenter in Narnia, Telmar is said to be located west of Narnia and the Western Wild and east of the Western Sea (“Telmar,” n.d.). These examples capture the biblical symbolism of the west, particularly in relation to the sea. Caspian’s name itself may come from the Caspian Sea, which is located between Asia and Europe and was under the rule of Nebuchadnezzar during the time of Daniel’s exile (Haeffele, n.d.).

Although Caspian X is a Telmarine, Aslan has made it clear that Narnia flourishes under human rulers who follow him, and Caspian ruling as king ushered in a new era of prosperity. Before his reign, due to fear and misunderstanding, the Old Narnians had all but been forgotten as the Telmarines who occupied Narnia sought to remove them from history. Through Caspian and the efforts of Narnians in the battle against the Telmarines, there was a reuniting in Narnia between the Narnians of old and all the inhabitants of Narnia who stayed after the war. Aslan was remembered and obeyed once more. As the west signifies a reuniting with God, perhaps this symbolism is being brought to life through Lewis’ depiction of Narnia following Aslan—a Jesus-inspired character—once more. (Lewis, 1950)

The East

This direction is rich in symbolic meaning. It is a point that helps us discern relative position due to its connection with the rising sun and may be connected to the concept of “beginning” (Lynley, 2016). In the Bible, references to the east are vast and meaningful. In Genesis 2:8, we learn that the Garden of Eden is located in the east; however, it’s important to recognize that the Land of Eden and the Garden of Eden are different and that the Garden of Eden is a distinctive area inside the Land of Eden. It seems that the east is largely attached to the meaning of holiness (Richoka, n.d.). In Genesis 3:24, its entrance looked east. When Adam and Eve were cast out of the Garden, celestial beings were placed on its east side. Genesis 4:16 has Cain going east yet again after the murder of his brother Abel, and eventually, humanity “migrated from the east” in Genesis 11:2-4. And, as mentioned before, the Tabernacle faced east. (Rodríguez, 2008)

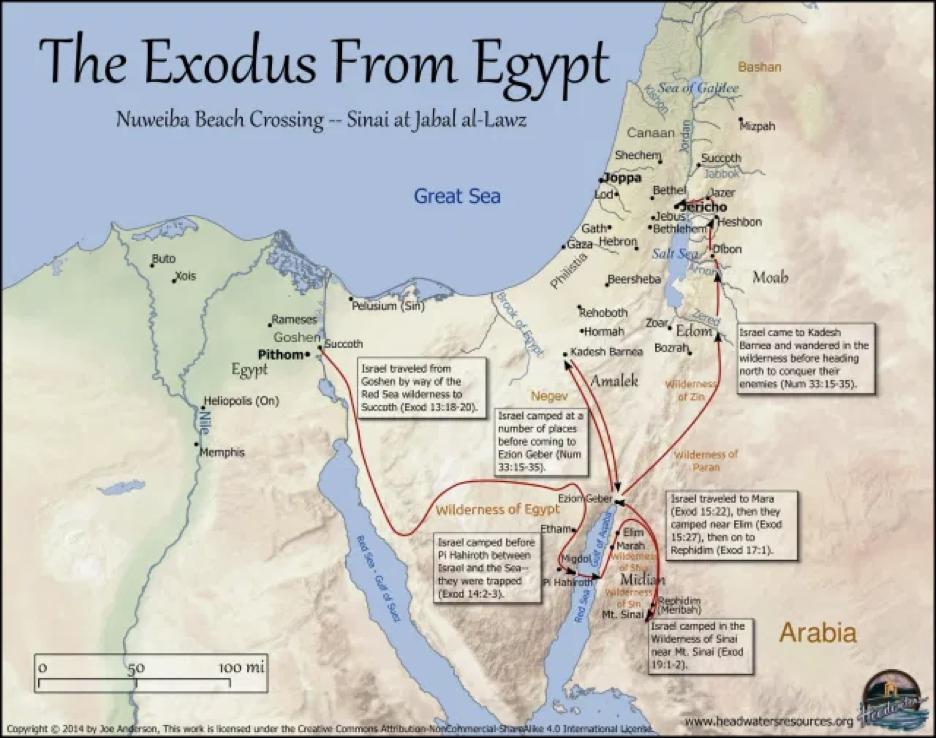

The east, as well, has both negative and positives meanings. The Garden being placed in the east may symbolize safety as well as holiness. However, after sin entered the world, moving eastward became a sign of exile or separation from God. Psalms 48:7 and Ezekiel 27:26 depict the east wind being destructive and violent and the east being a place of wilderness. Ezekiel 10:18-19 and 11:22-23 demonstrate the east as a symbol of the Israelites’ Babylonian exile—as Babylon resides east of Israel (see “Map of the Assyrian and Babylonian Captivity of Israel and Judah” above)—and, ultimately, their redemption by God’s hand. Revelation 16:12 and Isaiah 41:2 and 46:11 show that the east also represents God’s saving intervention (Rodríguez, 2008). Matthew 2:1-2 has the Messiah, Jesus Christ, being announced by the wise men coming from the east.

On a whole, it would seem that while the east consists of the good and holy—that which comes from the east is symbolically good—traveling east has a negative connotation. Traveling east aligns with alienation from God (moving away from Him) while traveling west is considered a reuniting with God (moving toward Him) (Richoka, n.d.).

Book Analysis: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

Once again, the connection between this book and the east is easily found. Prince Caspian and his crew are journeying out to the Eastern Seas to find the lost lords who had been sent by Caspian’s uncle, Miraz. Considering the lost lords were friends of Caspian’s father, it would seem that Miraz was fixed on removing any obstacles to his rule. In this way, the lords’ journey to the east could be representative of an exile.

Reepicheep, however, has a deeper reason in mind for his travels, saying, “‘As high as my spirit… Though perhaps as small as my stature. Why should we not come to the very eastern end of the world? And what might we find there? I expect to find Aslan’s own country. It is always from the east, across the sea, that the great Lion comes to us’” (Lewis, 1950, p. 433; emphasis added). In other words, much like how the Garden of Eden was in the east, Reepicheep is saying that Aslan’s Country is in the east and that Aslan comes (intervenes) from the east. This is fitting with the common allegorical thread of Aslan representing God and the biblical symbolism of the east. Aslan’s Country is a place of holiness, security, and safety. As well, Reepicheep took to sitting on the bulwarks of the ship and facing east toward his hopeful destination. Likewise, in Chapter 14, it is shown that Ramandu faces the east as they sing the sun to rise. The sun and its light are large aspects of the move toward Aslan’s Country, as it becomes larger and brighter the closer they get, alluding to the symbolism.

The main connection, of course, is Aslan’s Country residing in the utter east. When they arrive there, they are found by Aslan and reunited with him. While the aspect of going eastward is often symbolically a negative thing, it may be seen that in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Lewis is emphasizing facing Aslan and moving in the direction of his presence. (Lewis, 1950)

The North

This direction has a connotation of permanence and the eternal; this might be linked to a connection with the north star, due to its ever-presence in the night sky. Isaiah 14:13 states that God “sits on the mount of assembly in the far reaches of the north” (emphasis added) and Job 37:22 writes that “out of the north comes golden splendor; God is clothed with awesome majesty” (emphasis added). Ezekiel 1:4 mentions that “a stormy wind came out of the north, and a great cloud, with bright night around it, and fire flashing forth continually” (emphasis added). Therefore, the north may be symbolically linked to a dwelling place of God from which His magnificence (glory) comes down with both favor and righteous judgment. (Rodríguez, 2008)

As with most of the cardinal directions, there is an aspect of ambivalence—darkness to go along with the light. As the east was used for orientation, it was considered the forward-facing direction. The north, therefore, was considered the “left hand” and was symbolic of disaster. In Jeremiah 1:14-15 and Ezekiel 38:6, we see that God calls the lands of the north down to the people of Jerusalem and Israel to bring judgment upon the enemies of God’s people so that “the nations may know [Him]” when He “vindicates [His] holiness before their eyes.” Destruction and enemies, therefore, came from the north. In Daniel 11:21-45, God speaks to Daniel, telling of the false king of the north who “exalt[s] himself and magnif[ies] himself above every god, and shall speak astonishing things against the God of gods.” However, the false king’s reign, too, will come to an end. In this, God is described as the “true King of the North” (Rodríguez, 2008).

Book Analysis: The Silver Chair

It is not a large jump at all to be able to see the connection between the north as described in the above text and The Silver Chair. Firstly, Aslan tasks Jill and Eustace to go north, as this will lead them to where the lost prince has been captured and taken prisoner. Prince Rilian’s captor is the Lady of the Green Kirtle, who is said to have come from the north much like Jadis from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Likewise, Prince Rilian’s mother had been killed in the north of Narnia.

The Lady of the Green Kirtle is the enemy of the text with the representatives of Narnia being examples of “God’s people.” Where the Lady brings destruction—even to the point of plotting to wage war on Narnia—those who call upon the name of Aslan bring chaos into order. The Lady, who is called the “Queen of the Deep Realm,” may represent the false king of the north, spurning Aslan and creating a kingdom of darkness upon her name alone. Prince Rilian, instead, is shown as the “true king,” who honors Aslan with his words and deeds; the Lady, in her false reign, is ultimately struck down, and Prince Rilian takes his place on the Narnian throne. (Lewis, 1950)

The South

Symbolically speaking, the south is often depicted as negative, but due to its position from the directionally-orienting east, it also represents the “right hand,” which is spoken positively of throughout the Bible; therefore, it maintains the dark/light dichotomy held by the other directions. In Isaiah 30:6, we find that the south of Israel (the Negeb) was a wilderness of “trouble and anguish.” Likewise, Egypt, an oppressive land for the Israelites, was to the south. However, in Deuteronomy 33:2 and Exodus 19:1-2, we find that the Lord revealed himself to Moses at Mount Sinai in the south and journeyed with them from Egypt (the south). (Rodríguez, 2008)

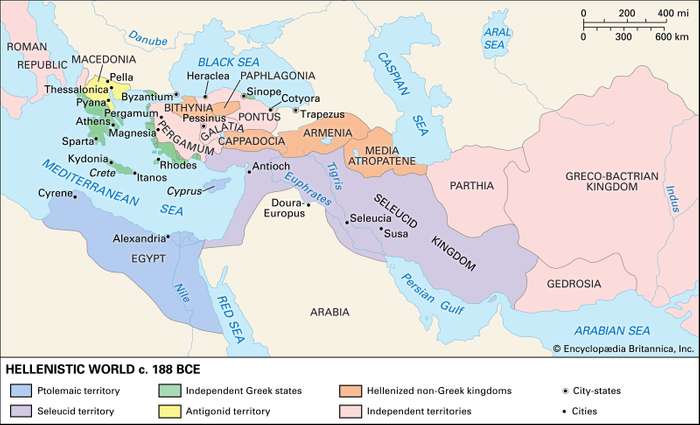

Prophecy on the “king of the South” and “the king of North” is depicted in Daniel 11. The prophecy seems to historically have found its fulfillment in the interactions between the Ptolemies (who were based in Egypt) and the Seleucids. Directionally, it is speaking south of Jerusalem (Treybig, n.d.-a, n.d.-b). While there could be plenty of discussion behind this prophecy and its meaning, the main concept that I would like to highlight is the oppression and war coming from the south.

On the other hand, the Messiah was said to come from the line of David, who was king of Judah, a tribe from the south (Kosloski, 2017). This, too, draws an interesting parallel to the Narnian book that best carries the symbolic meaning of the south, The Horse and His Boy.

Book Analysis: The Horse and His Boy

The fifth book in the Narnia series largely takes place in Calormen, a land in the south. Calormen is seen in stark contrast to Narnia, as they are described as a largely sexist, elitist, and polytheistic culture that maintains a social caste system and slavery; it would seem to be a steady representation of Old Testament Egypt, with Narnia being its Jerusalem archetype counterpart.

The Narnian characters of the book make it a point to distinguish themselves as “free” and different than those from the south. Bree, the talking Narnian horse who had lived most of his life imprisoned in Calormen as a warhorse, takes much time being concerned about what the horses in Narnia are like and if “bad habits” of the south have not rubbed off on him. He invited Shasta into this, as well, as he tells him to desist from adding “may he live forever” after saying the Tisroc’s—the head of Calormen—name, as they are “free” and not from the south. The Tisroc presents a Pharaoh-type character, or perhaps the south king like what was mentioned within Daniel. (Lewis, 1950)

When finding out that Archenland and Narnia are in danger, Shasta and his troop cross the southern desert, a wilderness—another tie to southern symbolism—at an exemplary pace to beat the Calormen army led by Rabbadash, the Tisroc’s son. Shasta can be compared to a Christ-type figure, a foreigner coming from the south to save Archenland from the destruction that Rabbadash brought with him. Or, perhaps, to draw it to the Old Testament, he can be seen as a Moses archetype. Shasta, an Archenlander who is actually an heir to the Archenland throne, was found in a boat as a baby by the river, taken in, and raised as a slave by a man of Calormen. Moses, who was also found in a basket at the river was raised by Egyptians, southern royalty. Shasta returns to his people of Archenland, delivering his true people from the southerners who raised him. Moses delivered the Israelites, his people, from their Egyptian oppressors. Likewise, while Moses met God in the burning bush and heard His statements of identity, Shasta spoke with Aslan with a similar discourse. When asked who Aslan was, Aslan responds with “myself” three times with three different tones of voice. We can see the connection to the “I AM” statement of the Bible. Therefore, the symbolism of the south may be able to hold a very distinctive relation to Exodus, which can thus be seen within the pages of The Horse and His Boy.

Finally, it could be seen that the prophecy in Daniel and its historical fulfillment may be fictitiously depicted in these pages. Narnia, as a Jerusalem-type, is caught in between the fight between Archenland, with King Lune as the “north king,” and Calormen, with Rabbadash as the “south king” role. While it can’t be known whether this was Lewis’ intention or not, it is a fabulously interesting thought to engage.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored the biblical symbolism of the cardinal directions and analyzed Lewis’ Narnian tales through that lens. While it’s difficult to know whether this was the intention of Lewis, it would seem that not only did he write each book with a particular direction in mind, he was also able to add depth to his tales by connecting to the biblical symbolism of those directions. Although this article only addressed the four cardinal directions, the expansive world of Narnia not only reached out to the four corners of the world but directionally across time, too. This was an insanely fun topic to dive into, so if someone is interested in an analysis of the remaining three books in regards to the genesis book and chronal direction, then let me know in the comments, and I may write something up.

In a time when we are less conscious of the cardinal directions, it makes sense that we may not be aware of the possible symbolism that many cultures attribute to these guideposts. The Bible remains to be one of most influential texts in the world—and I would argue the most influential text—and, unfortunately but understandably, its mysterious nature may cause some people to look upon it with doubt and caution, not wishing to dive into it too closely due to potential confusion or lack of interest. As Christians, while we must be grounded in our theology and must do the work to make sure that we do not lose sight of the essential beliefs of Christianity, I think we often miss the opportunity to be playful before the Lord. I think we miss the opportunity to stir up our affections for Him by thinking about how every word of the Bible has meaning and a reason. We are given glimpses of his majesty as He reveals himself to us in different ways, and I believe that thinking upon the symbolism and interpretation of the Bible opens us up to awe. He has given us the freedom to explore and given us the Holy Spirit to guide us in our exploration, and while there should be caution and respect involved, we ought not to ever feel burdened by the Bible.

References

- Anderson, J. (2014). Exodus route map [Online image]. Headwaters Christian resources. https://headwatersresources.org/exodus-route-map/

- Christopher, J.R. (n.d.). Planet Narnia: The seven heavens in the imagination of C.S. Lewis. Mythopoeic society. http://www.mythsoc.org/reviews/planet-narnia.htm

- Haeffele, J. (n.d.). Daniel 7: Four beasts and the little horn. Life, hope & truth. https://lifehopeandtruth.com/prophecy/understanding-the-book-of-daniel/daniel-7/

- Hellenistic world c. 188 BCE [Online image]. (n.d.). Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ptolemaic-dynasty

- Kosloski, P. (2017). The ancient symbolism of North, South, East, and West. Aleteia. https://aleteia.org/2017/08/04/the-ancient-symbolism-of-north-south-east-and-west/

- Lewis, C.S. (1950). The chronicles of Narnia. HarperCollins Publisher.

- Lezard, N. (2010). Planet Narnia: The seven heavens in the imagination of CS Lewis by Michael War. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/jun/19/nicholas-lezard-paperbacks-narnia-ward

- Literature / The Chronicles of Narnia aka: Narnia. (n.d.). Tvtropes. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Literature/TheChroniclesOfNarnia?from=Literature.Narnia#:~:text=

The%20next%20four%20books%20cover,The%20Horse%20and%20His%20Boy. - Lynley. (2016). The symbolism of cardinal direction. Slap happy larry. https://www.slaphappylarry.com/the-symbolism-of-cardinal-direction/#:~:text=North%20%3D%20

disaster%2C%20represented%20by%20the,%3D%20cold%2C%20wintry%2C%20inhospitable. - Map of the Assyrian and Babylonian captivity of Israel and Judah [Online image]. (n.d.). Conforming to Jesus. https://www.conformingtojesus.com/charts-maps/en/assyrian-babylonian_captivity_map.htm

- Map of the journeys of Abraham [Online image]. (n.d.). Bible history online. https://www.bible-history.com/maps/6-abrahams-journeys.html

- Planet Narnia. (n.d.). Planet Narnia. http://www.planetnarnia.com/planet-narnia/

- Richoka. (n.d.). 2:21: The signifance of the direction “east” in the scriptures. Messianic revolution. https://messianic-revolution.com/2-21-significance-direction-east-scriptures/

- Rodríguez, Á.M. (2008). The symbolism of the four cardinal directions. Biblical Research Institute. https://adventistbiblicalresearch.org/materials/archaeology-and-history/symbolism-four-cardinal-directions

- Telmar. (n.d.). In The chronicles of Narnia wiki. https://narnia.fandom.com/wiki/Telmar

- The instructions and dimensions of the Tabernacle [Online image]. (n.d.). Blue letter Bible. https://www.blueletterbible.org/Comm/smith_don/PortraitsofChrist/PortraitsofChrist/poc-013.cfm

- The Seven Heavens. (n.d.). Planet Narnia. http://www.planetnarnia.com/planet-narnia/the-seven-heavens/index.html

- Treybig, D. (n.d.-a). The king of the north. Life, hope & truth. https://lifehopeandtruth.com/prophecy/understanding-the-book-of-daniel/the-king-of-the-south/

- Treybig, D. (n.d.-b). The king of the south. Life, hope & truth. https://lifehopeandtruth.com/prophecy/understanding-the-book-of-daniel/the-king-of-the-south/